关于美元的浅显对话

最近读到曼昆的宏观经济学,第32章P231录入了Christina D. Romer的一篇文章《关于美元的浅显对话》,为这位经济学家的直言不讳所打动。在纽约时报官网上找到了原文,记录下来,勤加研读。

原文地址: https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/22/business/economy/22view.html

AT a recent news conference, Ben S. Bernanke, the Federal Reserve chairman, was asked about the falling dollar. He parried the question, saying that the Treasury secretary was the government’s spokesman on the exchange rate — and, of course, that the United States favors a strong dollar.

Listening to that statement, I flashed back to one of my first experiences as an adviser to Barack Obama. In November 2008, I was sharing a cab in Chicago with Larry Summers, the former Treasury secretary and a fellow economic adviser to the president-elect. To help prepare me for the interviews and the hearings to come, Larry graciously asked me questions and critiqued my answers.

When he asked about the exchange rate for the dollar, I began: “The exchange rate is a price much like any other price, and is determined by market forces.”

“Wrong!” Larry boomed. “The exchange rate is the purview of the Treasury. The United States is in favor of a strong dollar.”

For the record, my initial answer was much more reasonable. Our exchange rate is just a price — the price of the dollar in terms of other currencies. It is not controlled by anyone. And a high price for the dollar, which is what we mean by a strong dollar, is not always desirable.

Some countries, like China, essentially fix the price of their currency. But since the early 1970s, the United States has let the dollar’s value move in response to changes in the supply and demand of dollars in the foreign exchange market. The Treasury no more determines the price of the dollar than the Department of Energy determines the price of gasoline. Both departments have a small reserve that they can use to combat market instability, but neither has the resources or the mandate to hold the relevant price away from its market equilibrium value for very long.

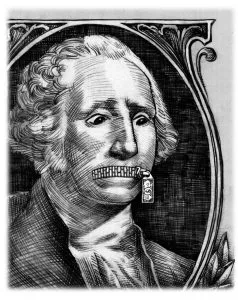

In practice, all that “the exchange rate is the purview of the Treasury” means is that no official other the Treasury secretary is supposed to talk about it (and even he isn’t supposed to say very much). That strikes me as a shame. Perhaps if government officials could talk about the exchange rate forthrightly, there would be more understanding of the issues and more rational policy discussions.

Such discussions would start with some basic economics. The desire to trade with other countries or invest in them is what gives rise to the market for foreign exchange. You need euros to travel in Spain or to buy a German government bond, so you need a way to exchange currencies.

The supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market comes from Americans who want to buy goods, services or assets from abroad. The demand for dollars comes from foreigners who want to buy from the United States.

Anything that increases the demand for dollars or reduces the supply drives up the dollar’s price. Anything that lowers the demand for dollars or raises the supply causes the dollar to weaken.

Consider two examples. Suppose American entrepreneurs create many products that foreigners want to buy, and start many companies they want to invest in. That will increase the demand for dollars and so cause the dollar’s price to rise. Such innovation will also make Americans want to buy more goods and assets in the United States — and fewer abroad. The supply of dollars to the foreign exchange market will fall, further strengthening the dollar. This example describes very well the conditions of the late 1990s — when the dollar was indeed strong.

Now suppose the United States runs a large budget deficit that causes domestic interest rates to rise. Higher American interest rates make both foreigners and Americans want to buy more American bonds and fewer foreign bonds. Thus the demand for dollars increases and the supply decreases. The price of the dollar will again rise.

This example describes conditions in the early 1980s, when President Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts and military buildup led to large deficits. Those deficits, along with the anti-inflationary policies of the Fed, where Paul A. Volcker was then the chairman, led to high American interest rates. The dollar was very strong in this period.

Both developments — brilliant American innovation and troublesome American budget deficits — caused the dollar to strengthen. Yet one is clearly a positive for the American economy, the other a negative. The point is that there is no universal good or bad direction for the dollar to move. The desirability of any shift in the exchange rate depends on why the dollar is moving.

It also depends on the state of the economy. At full employment, a strong dollar is good for standards of living. A high price for the dollar means that our currency buys a lot in foreign countries.

But in a depressed economy, it isn’t so clear that a strong dollar is desirable. A weaker dollar means that our goods are cheaper relative to foreign goods. That stimulates our exports and reduces our imports. Higher net exports raise domestic production and employment. Foreign goods are more expensive, but more Americans are working. Given the desperate need for jobs, on net we are almost surely better off with a weaker dollar for a while.

Fed policy is determined by inflation and unemployment in the United States. But if Mr. Bernanke could discuss the exchange rate openly, he would probably tell you that one way any monetary expansion helps a distressed economy is by weakening the dollar. That is taught in every introductory economics course, yet the Fed is asked to pretend it isn’t true.

Likewise, fiscal policy is determined by domestic considerations. But trimming our budget deficit, as we should over the coming years, would also weaken the dollar. And that, in turn, would blunt the negative impact of deficit reduction on employment and output in the short run.

STRANGELY, every politician seems to understand that it would be desirable for the dollar to weaken against one particular currency: the Chinese renminbi. For years, China has deliberately accumulated United States Treasury bonds to keep the dollar’s value high in renminbi terms. The United States would export more and grow faster if China allowed the dollar’s price to fall. Congress routinely threatens retaliation if China doesn’t take steps that amount to weakening the dollar.

But in the very next breath, the same members of Congress shout about the importance of a strong dollar. If a decline in its value relative to the renminbi would be beneficial, a fall relative to the currency of many countries would help even more in the current situation.

To say this openly risks being branded not just an extremist but possibly un-American. Perhaps it is time for a more adult conversation. The exchange rate is the purview of market economics, not of the Treasury or strong-dollar ideologues.

Christina D. Romer is an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and was the chairwoman of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers.